Memories of Rainham Past by John Austin

To my way of thinking Rainham has never been the same since the old C. of E. School with its flint walls, outside staircase and turret bell-tower at the top of Station Road (once White Horse Lane) was pulled down. Fortunately the Church still dominates the skyline. During 2020 Action Forum featured memories of growing up in Rainham from several widely-spread correspondents. I was born in a cottage still standing at the lower end of Maidstone Road, for many years known as Bredhurst Lane. My birth certificate records the district as ‘Gillingham’ but six years earlier it would have been stamped ‘Milton Regis’. Regis means royal: Milton had been owned by Kentish Kings as far back as William the Conqueror. Why the change? Prior to 1929 Rainham had its own Water Board, and a Fire Service dating back to 1901 — but no main drainage.

In that time the population of Rainham had almost doubled, and as growth continued it was feared that current methods of emptying privies were contaminating the subsoil in some areas. Milton Rural Council considered that extending their own drainage system as far as Rainham would cost over £20,000, far too expensive for Rainham to afford. There had already been suggestions from Rainham’s Parish Council that the small town should amalgamate with the neighbouring Borough of Gillingham, which had a population of 57,000. Gillingham Council agreed. Although this would mean an increase in rates for Rainham’s citizens, the proposal also offered other advantages including Widening the High Street and building a Town Hall, so the deal was settled.

Photo showing the school at the top of Station Road

In 1939 my parents had just completed the purchase of a house at what was then the lower end of Hawthorne Avenue; there were then only fields of cabbages and potatoes beyond. So when I started school at the beginning of 1940 it was at Twydall lnfants. Frank, a couple of years older, attended Byron Road School. Though it was only about half a mile from our home as the crow flies, there was no direct path; I had to walk up to the A2, turn right as far as Twydall Lane, then north down to Romany Road - about 1‘/1 miles. Frank’s joumey was even longer, and we had to make the journey four times a day. A campaign begun by my mother and her neighbour for a more direct route eventually led to a proper footpath across the allotments to Romany Road.

The period between September 1939 and May 1940 became known as the ‘phony war’. No bombs fell, but gas masks were issued, ration books introduced, air raid shelters were erected and sandbags piled up round important buildings. Early in 1940 Andersen shelters, in the form of corrugated iron sheets, were delivered by the council to Hawthorne Avenue. There was no charge for families where the husband or father, like ours, was in the Forces. But how was Mum to dig the hole, which needed to be three feet deep? Fortunately the two teenage sons of the Howland family from Pump Lane came to the rescue. Mum herself, after a brief lesson in brick-laying from Mr Howland, built the blast wall in front of the entrance.

The phony war ended abruptly at the end of May with the mass evacuation of troops from Dunkirk. l can just remember standing near the viaduct in Pump Lane watching the Red Cross trains go by,

but of course did not appreciate their significance. As the Battle of Britain raged over East Kent in late summer most people were not expecting air raids on London or beyond — they still thought the war

would be over by Christmas. With Dad away, Mother and the two of us were left on our own in Hawthorne Avenue. Her sister Ethel, who lived in Ealing, thought we might feel lonely, so invited us

to join her family there. The house in Hawthorne Avenue could be let. Aunt Ethel’s house, one of a pair of semi-detached houses, was already fairly full. As well as her husband, who was something in the city, going

off each morning with a rolled-up umbrella and a bowler hat, but medically unfit for active service, there were also their daughter Joy (14), Cousin Renée (18) and Grandad, in his mid-70s. Mum

was fitted in somewhere, but Frank and I slept next door. This half of the pair was occupied by Mrs Gardiner and her son Derek: her husband too was away in the Forces.

Frank and I had just a short spell at school in Ealing. We were sometimes escorted by Joy and her friend Honor Blackman, who would later become famous for her roles as Cathy Gale in ‘The Avengers’ and as Pussy Galore in ‘Goldfinger’. Soon we were taking shelter under the stairs as raids reached Ealing, and it was during one raid that the doorbell rang, and Aunt Ethel opened it , expecting an ARP Warden saying we were showing a chink of light. But it was my father, in his Chief Petty Officer’s uniform, on a very brief leave. The four of us were able to have a photograph taken in a local park, but what I really remember about his visit was the clockwork train set he had brought with him from Hamleys. Not long afterwards a landmine blew the roof off the two houses, though none of the residents were hurt. Mum temporarily rented a nearby house — but then the school was also hit.

Before he left Dad had told Mum to ensure our safety by taking advantage of the evacuation plans for school children which came into action in October 1940. Frank and I were sent to

Cornwall where we were billeted at a farm. The place had hardly changed since the end of the previous century — no piped water, electricity or main drainage. The privy was at the bottom of

the garden. Very occasionally my mother was able to manage a visit, for she was now working at home back in Hawthorne Avenue (she had been Warned by a neighbour in Kent that the

tenants there had done a moonlight flit, leaving it in rather a mess) for the Royal Navy. Her job was attaching collars to naval uniforms, delivering them to the Dockyard when a batch was complete. But

following a visit in Spring 1942 she realised that we were not being adequately fed or schooled, and immediately took us back to Hawthorne Avenue. But now Twydall schools were full, and we were

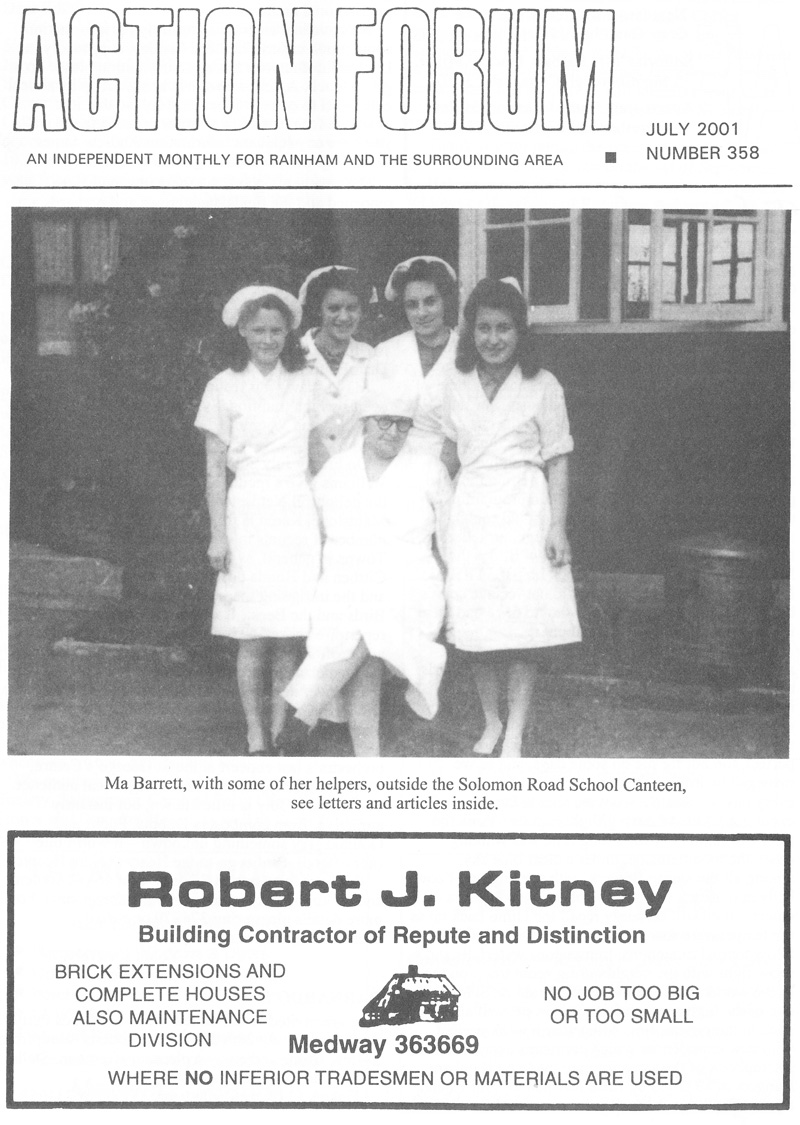

allotted places at the Council School [later Meredale] in Solomon Road. Those of us who went there remember affectionately our caretaker, Mr Barratt, who would ladle our morning milk

ration from a churn into our tin mugs. His wife was the redoubtable Ma Barratt.

We boys were able to have our dinner at the only school canteen in the area which was actually sited in our playground. Dinners cost 3d each, but were well worth the price because it meant more rations

for mums struggling to feed children at home. At that time it was not overwhelmed by numbers, but as more and more children sought places restrictions had to be brought in. Only pupils living

more than a mile away from the canteen were eligible for the meals, and those from the senior school who lived in Upchurch or Lower Halstow had priority. Because our mother was working, and

the length of our daily trek the two of us were still allowed to have our mid-day meal there when we moved to the Senior School in Orchard Street at about the age of ten. Here our morning milk came in one-third pint bottles, issued by the caretaker Mr Dunn. At the end of morning and afiemoon school he would exchange his boiler suit for his police uniform and become Special Constable P.C.Dunn. Stationed at the junction with the High Street, he made sure children crossed the main road safely.

En route to the canteen we straggled down past the blacksmith where we might catch sight of a shire horse being shooed or a red hot metal rim being fitted on to a cart wheel, then crossed the main road

to Station Road. (The barbers at No. 47 charged only 4d. for a boy’s haircut as opposed to 9d. in the High Street.) Opposite Webster Road, by the terminus of the No. 2 buses of the Chatham and District Motor Company in their brown and cream livery, we passed the ironmonger’s shop where pots and pans dangled in the doorway. As we turned into Solomon Road the whiff of our dinner became gradually more pungent as we approached the canteen. This was a long wooden hut in the playground, very close to the railway, and it shook with every passing train. The smoke from the engines, mixed with steam from the kitchen, could make the room quite foggy. In charge of the band of cooks, all ladies who had served there since it had opened, was Mrs. Barratt, more often known as ‘Sergeant Major’ or ‘Ma’ Barratt. She was not very tall, but had a voice that could be heard across the playground when telling us to get into our two lines, boys and girls separately. When I wrote about her in Action Forum in May 2001 (AF 356) I had many phone calls and personal visits from others who remembered her with mixed feelings.

At the door we had to extend our hands, which had to be clean enough to pass her inspection, before being allowed inside. If they showed signs of ink or paint, we were sent to scrub them before rejoining the queue at the back. (It was rumoured that even teachers had to show theirs.) Once into the hall her voice level dropped dramatically as she commanded us ‘Now say your grace, dears’ and we dutifully mumbled ‘For what we are about to receive may the Lord make us truly thankful’. But then it was back to her usual pitch - ‘Elbows off the table’. ‘Sit up straight’. ‘No talking’. We sat on forms, twelve to a table, and a boy at the end might be deposited on the floor if all his neighbours stood up at once while he was still seated. Teachers sat at a separate table which was covered by a white tablecloth.]

The operation was run like clockwork. We were allotted only half an hour to eat, and of course had to finish everything on our plates. The food was filling if not exciting. We might have shepherds

pie made with mince, stew, well-boiled cabbage and swede, followed by milk pudding with a dob of jam, chocolate pudding or, our favourite, jam roly-poly and custard. These were boiled in long cloths. The meat in the stew wasn’t top quality, and one cheeky pupil offered to Mrs Barratt a dead cat he’d seen on his way to school. This earned him a telling off and a cuff round the ear. There were two varieties of milk pudding, semolina or tapioca. Supplies of the latter, made from cassava root imported from South America, were apparently limitless even after the war ended. I have avoided milk puddings ever since.